This was cut for length from my paper. It is too detailed. You may enjoy it here.

Ideation - Daydreaming

The seed for this project was planted in 2023 when I was first applying to graduate school, trying to decide how I wanted to spend the first next few years of my life and what I wanted to create to represent myself going forward. Like many of my projects, ontological bleed started with a survey of resources and a curiosity about atypical narrative structures.

I'm an interdisciplinary artist, and I like to make a lot of things, and I like to tell a lot of stories and a lot of different formats. One of the things that I really wanted to explore is how different narrative formats can tell stories, and what their different affordances are - an illustration is a different sensory experience than a poem or a video game, each has their strengths in what they can reveal and focus about an event, and inform how the story told will unfold from these constraints. My original research question in 2023 was about trying to combine the storytelling methods together - to tell one story, with every chapter in a different format and to write a paper that would compare the affordances of each. Specifically, to discuss how “close” they feel to our own reality, and how far they can draw us out of our own reality and into theirs. I was referring to this as “narrative distance”, and I was especially concerned with stylization and suspension of disbelief.

I decided the best way to showcase these disparate storytelling formats was in a database simulation game to allow for non-linear exploration and have players make their own connections. The software would be shown in a physical installation with the artwork that it documented, allowing players to cross-reference the originals. If physical art has an aura, I wanted to keep it, so it could be experienced in person, not just mediated by digital documentation.

As I continued mulling over it for the next few years waiting for my graduate program to start, I became more interested in examining the database interface simulation aspect of the project itself - not just as a framing device, but as its own rich narrative format. A research database can contain artifacts that tell stories on their own, but a great deal of the storytelling takes place on connections between them, and augmented by the annotations left on them. Some of my favourite literary media, while not databases, contain footnotes of different characters commenting on the action asynchronously, and even on each other. A database allows this, and allows these annotations to become virtual bodies or disembodied voices of these characters. It can also allow a conversation to be presented with parts of it missing, waiting to be unlocked, preserving the mystery for later.

My engagement with this work remained purely conceptual for a very long time - without contextual academic research or fabrication, it lived in my head and on paper for around two years. I daydreamed and wandered and pulled everything I came across into this project - marking down notes of the different plans of attack I could take, and the different concepts I could express in this format. The amazing thing about being an artist is looking at the world is something you can eat - looking at other people's arts and thinking: I love this, I will make my own, this is mine now.

Drafting - Early Research

Through my early research for my annotated bibliography I discovered much of what I discussed in my contextual review. It brought me further away from thinking about narrative the way I had been - about what information it gives players access to, and more about how it moves players through different ontological realms from their own life into the world of the fiction. This is a bit of a higher level abstractation than just: how do my narrative tools inform what I can show or tell, and places more focus on - what is the experience: how does a player feel, who do they become? It becomes more about how those narrative structures support this specific experience over the broad features of the structures themselves, and gives me a direction for what experience I wanted them to have. The story was always going to be speculative fiction - but as I looked through the discourse into how other worlds and haunted houses work in fiction, I became enamored with the idea of making the story itself explore the way these boundaries work as we experience them.

I really fell in love with researching. It felt like playing an open world videogame, hunting through databases and keywords and people's names, searching for clues to fill in the gaps in an argument that I was building. Bringing home artifacts to file into my own databases, to stitch back together with my own connections, often leaving a mess I would need to go back and clean up later.

Framing - Early Prototypes

Over the summer I began prototyping, both in software and in physical media.

Most of the games that I've created have been built in the Unity game engine - I've been working with it for about 12 years. For this game, I decided I wanted to try something different. Unity games are clunky beasts that immediately announce themselves as a game, and I wanted something that could pass as an innocuous interface more convincingly. What would actual database software use? I landed on using HTML and JavaScript, which I had been playing around a bit with in one of my classes, using Electron, which is a framework that allows HTML to be packaged as stand-alone software. In my teens and twenties, I did a lot of experimentation with websites, interactive comics and experimental animation using combinations of HTML. CSS. JavaScript and PHP, and even dabbled a bit as a web designer after my undergraduate degree, so I recognized I was hobbling myself a bit, but it wasn’t like I was starting from scratch.

At the same time I was digging through ResearchGate and the OCADU library for narratology research papers, I was digging through GitHub and stack exchange for examples of JavaScript powered database software repos that I could use as a base for my game. I had imagined that a media database would be a common enough software that I'd find dozens, if not hundreds, of working examples that I could simply build my fiction on top of.

To my enormous frustration this did not end up being the case - any examples that I found that did anything like what I needed were hopelessly obsolete, as was my own decades old technical knowledge.

I found Electron impenetrable, and the boilerplate repository that I found - the only one that I could get working in a development environment, depended on React and Typescript frameworks that I grew to loathe. I eventually ended up stripping all of the Typescript from the project, its additional grammar just made it too difficult for me to understand and learn what I was doing. To this day I'm still tempted to go through the project and rip out all the React and work with vanilla JavaScript - but it has its benefits and I hope they eventually outweigh the drawbacks.

TODO: Images went here.

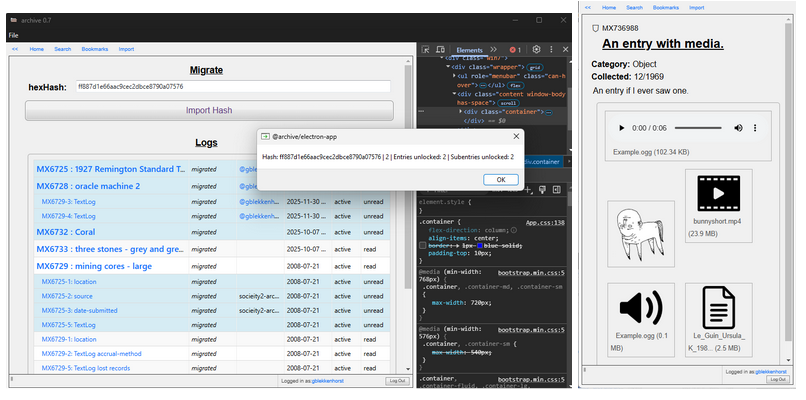

Editable database with some CSS trickery. The database can be exported and imported, and reset to a specific gamestate.

An important aspect of this project, to me, is that the software I’m building is not exclusively an interface for the player to experience the world I’m building. It is also an interface for me to do the building. The software has an ‘admin’ mode, to to write the actual entries, change their metadata. It becomes its own game engine, and allows for me to change the shape of the interface as I’m writing to support what it says, and changes the shape of the story. This made it vitally important that the software itself was structurally sound before too much content was poured through it, less the story be accidentally wiped out from some instability. During this era, I managed to develop a workflow to keep my data safe and backed up, and tried to work out the bones of the story in broad shapes off-screen.

I did more digital material exploration, digging into technologies to create my reflection development blog, and ended up using a Digital Garden plug-in for my notetaking software, Obsidian. As a material, it has a significantly lower learning curve than the security obsessed React framework I was struggling with. It also had me going back over the random scraps I’d written to myself over the last two years and mentally reprocess them.

I was able to take a class that allowed me to experiment with a lot of different sculptural formats - although at the time the fiction of the game was not advanced enough to allow me to begin drawing it out through these materials.

At this point, I was still very, very stuck on what I was actually making. I knew what I wanted it to make, and I knew how I wanted players to feel, but I didn't know the plot. I didn't know what I needed to make in terms of artifacts to represent that story. I didn't know who any of these characters were yet - and whenever I tried to spend time in that realm of thinking, I felt like I was hitting a wall at every turn. There was no heart yet, and this was very disheartening . I was very self-conscious when compared to existing media - so worried that my story would feel cheesy and cheap.

I tried a lot of different things to try to force myself into the fiction - revisiting my favourite media, generating long lists of impossible timelines, building randomization systems to try to generate connections between the floating nodes I had hanging around in my imagination.

TODO: Game to make a game images here.

A game to make a game. The game includes details I want my story to include, and solo TTRPG mechanics to generate connections and weight between them.

By the end of the summer I had a rough skeleton of a database with no story, no characters, and no artifacts. What I thought I’d be able to accomplish in a weekend had taken me 4 months. Maybe I could have cut down this timeline if I wasn't learning a new language - if I'd worked in Unity, would I be much further along? But I do feel by taking the leap of working in this alien material, I became more mindful of how it worked in ways I otherwise would have taken for granted, and seen opportunities for narrative exploitation I would have missed if I hadn’t been stuck.

I started and abandoned several different Git repositories. Working with code is such a strange material - it feels like something halfway between shuffling papers and building rooms that engulf you. You enter and leave, moving between them adjusting furniture, painting walls, running cable that will light up or black out other rooms in ways you won’t discover until the next time you visit them. Sometimes it's best to scrap everything and start over in a new empty house with a better foundation.

TODO: Dual moniter images

On a dual monitor, you can see the software’s insides, its outsides, and a timeline of everyone it has been, all at the same time.

By the end of the summer I had a structure that could be built on, synced on two separate computers - clones of each other that would sometimes drift apart and need to be merged. You go to sleep and you dream in code and you wake up, rushing through your morning routine so that you can get back into that house and install all the things that you thought of while you were asleep.

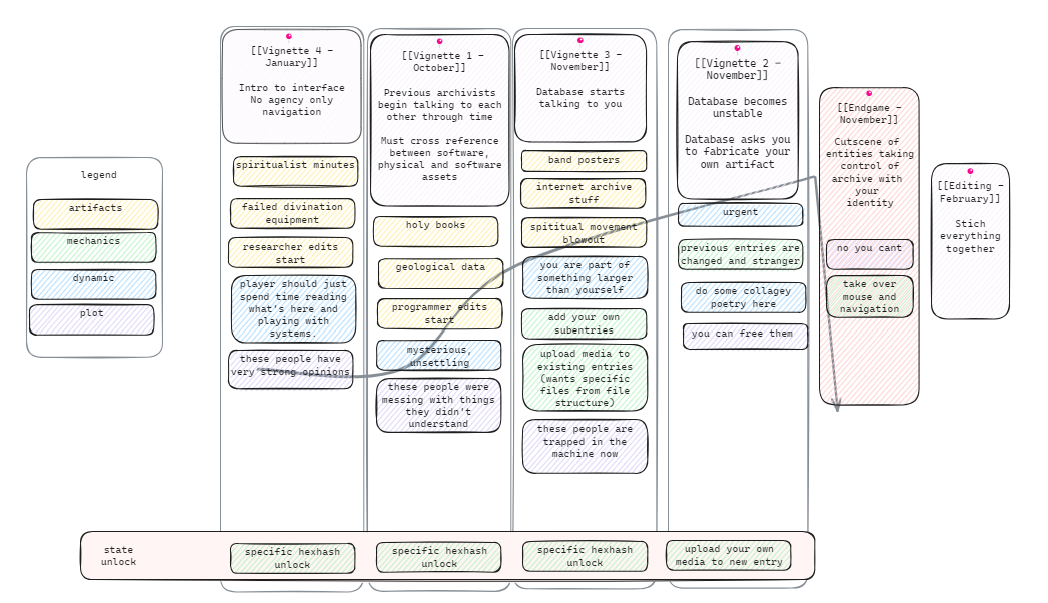

Working on this thesis project at this point felt like I was trying to eat an entire elephant at once. I decided at this point, that rather than building towards one giant final exhibition, I would break the story up into shorter chunks, so I could set furious deadlines for myself to complete shorter contained experiences. I refer to them as vignettes rather than chapters - they are not linear, and each is a standalone story in the world with its characters. Playtesting the installation is time-consuming and cumbersome, and the vignette structure elevates each opportunity to present it as a completed artwork. The fragmentary nature of the database allows the software to simply deactivate the parts that aren’t currently in use. These separate stories can be stitched back together in their time, and each step doesn't need to be weighed by its path through the whole, but only its paths to its neighbors.

Early layout of the story structure and timeline for development.

Walls and Floors - Vignette 1

With my skeleton working, I spent the next few weeks working towards my first vignette.

I burnt a lot of time trying to implement features that didn't work and I had to bail on - namely having media saved to the hard drive instead of getting loaded into binary where they slowly corrupted, getting the registration page working, and second window to hold the terminal.

TODO: Image here of media working

In early prototypes, the media became corrupted every time the database was reprocessed by the software. Sometimes this created beautiful glitch artifacts, but most of the time it just made the images shorter and shorter until they disappeared.

The slow erosion of the media data was apt to the fiction, but not ideal in practice - I would need to control what data was kept and that was lost if players had any hope of finding their way through the information. But seeing the way data can erode and corrupt in real time was as charming as it was annoying.

Towards the beginning of this process I had a breakthrough with the fiction that is difficult to describe - I collected some mining cores in my mothers home town, and I audited a class about the history of writing that introduced me to the concept of spirit or oracle machines. I had always known that the game would be about entities that frantically reach into our world to blindly insert themselves into our physical reality. But I didn't know what the archive actually was, why humans made it, and why it happened to document these intrusions - I was considering archeology, but somehow that felt somehow both too limited and not specific enough. The oracle machines, and the idea of humans experimenting with different technologies to give voices to the disembodied gave me the idea that this archive could be about one of these spiritualist societies - what they collected as evidence, the things that they built, and the people who came later who were curious about what they were trying to accomplish.

The mining ores gave me the idea that I can roughly break up each vignette by different earthly eras, and consider things like biology and geology as forms of technology the entities have tried to exploit, in the same way the spiritualists were experimenting with typewriters and telephones, on a much longer timescale. This theme would not necessarily be explicit to players, it would just give me some structure in where the story goes as I'm writing it.

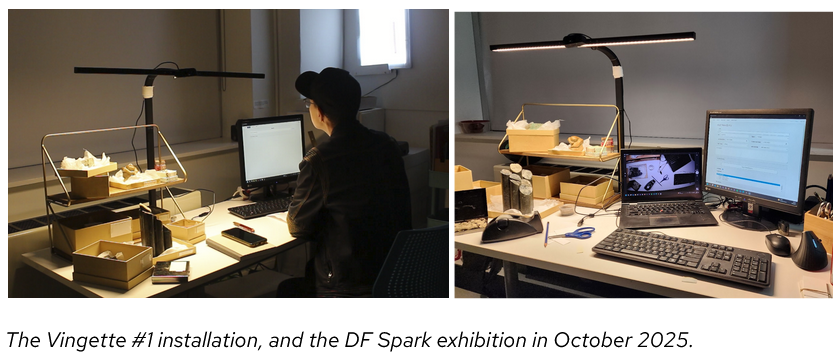

In Vignette #1, I had some specific conceptual simulation I wanted to include. I wanted to represent the very beginnings of the player entering the fiction (metalepsis) and handing over a part of themselves the gain entry (bleed), by providing a very rudimentary login page, asking players to choose how they will be represented in the game world. Everything they do there afterwards is visibly logged with their username and a time stamp of the moment they committed an action in the software.

The migration mechanic was originally intended to have players searching for hexhashes in another software, but for this deadline, the secondary software would not be completed in time. (I like the word hexhash because it has the word hex in it, and because it is a magic word in a language you don’t understand but the computer does - you must participate in a ritual with mysterious mechanics to achieve an end you can only guess at before committing to.) I compromised by having players search and copy the hexhashes from a spreadsheet. This still achieved the result of having the world bleed out from being contained by a single piece of “game” software, and playtesters seemed to settle into a flow of hunting and unlocking information. I was surprised by how many people committed to playing the entire thing, a 10-15 minute experience, and that they engaged with the narrative to the degree that they shared with me how it related to their experiences and interests afterward. I had always worried the public setting would make it difficult for players to care or concentrate on plot, but this did not end up being the struggle I expected, at least in the context of a digital futures student exhibition.

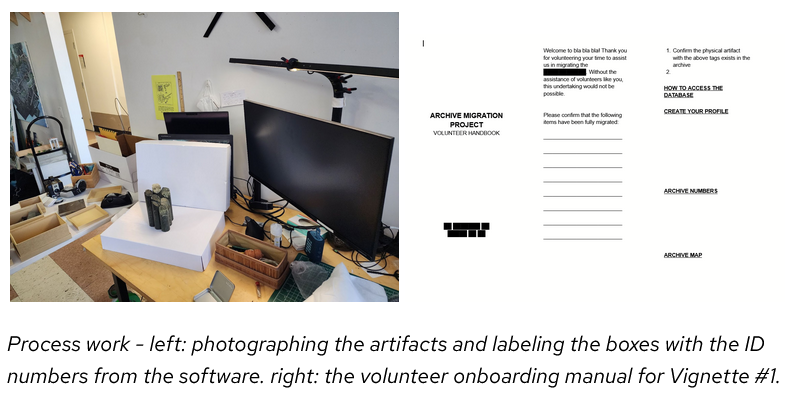

Another conceptual touchpoint I wanted to represent was encouraging metalepic experience by drawing the gameworld out into the physical world. I wasn’t sure I could get this done by this deadline, but like many things you don’t expect, this came together very quickly once the gates were open. Including physical artifacts - at this point, objects I happened to have around - gave me anchor points to write the fiction around and seeing them reflected on the computer screen next to the physical installation made them feel haunted. Luckily, in addition to the mining cores, I happen to own a lot of rocks. (I love rocks.)

I wasn’t intending to do the onboarding manual until much later, as it was more intended as an advertisement for the digital version, and a physical artifact for players to mark up and have as a keepsake of their experience. But realized at the last minute it could also function as a tutorial for how to play the game, which was immediately needed. Having players need to cross reference a paper manual (or, eventually, a PDF) to find their way is another method of drawing the fiction out of the software and into the world around it, a delightful discovery. In practice,players needed a lot of prompting to read it, most people moved it aside and beelined for the monitor. They were willing to read large chunks of text on the screen but very few looked at the paper, or for that matter, touched any of the artifacts.

The exhibition went very well, and while I was unable to collect experience data, I was able to find weak points in the design to address in future iterations, and have a proof-of-concept that my design was an engaging and functional experience.

Plumbing and Electrical - Vignette 2

Vignette #2 was again consumed by dealing with structural problems - the issue of media degradation continued to plague me. I did eventually figure out how to have media saved into the software without being translated and corrupted by the JSON save system, and I could finally focus on quality of life fixes both for the player experience, and for me as an author. Writing the story was finally becoming something that is fun and pleasurable to do.

This vignette will focus on modeling two important concepts as mechanics - allowing unlocking entries to trigger other changes in the software without the players intention, and for one of these changes to having the software address the player directly, and provoke them into forging their own artifact to upload into the system.